Raised by Wolves

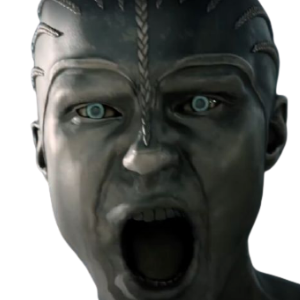

This show is good stuff, watch it! :: NO ONE IN HBO Max’s new science fiction drama Raised by Wolves is who they used to be. Humans have flung themselves from a decaying, technologically advanced society to a deserted planet where they grow tubers and scrabble at fungus. Religious order and hierarchy have been replaced by chaos as hardship and whispering voices unspool faith. Children kill their innocence for food. People surgically alter their faces. Androids have been hijacked and reprogrammed, and cobble themselves back together with pieces they rip from the squelching, milky-blooded bodies of the fallen. All of this, they insist, is necessary: for survival, for a god, for the preordained bright new future.

Raised by Wolves follows parallel attempts to save humanity from itself. First, there are Mother and Father, two androids dispatched by their creator to raise human children to be pacifist atheists after religious wars destroyed Earth. After landing on Kepler-22b, they farm and weave their own clothes from rough fibers. Father has been programmed to tell them dad jokes, but life is harsh. They’re joined by the last remnants of the civilization they’ve fled and been taught to abhor—an ark full of the Mithraic, a militaristic religious group with a fondness for mullets and crusader-style tunics who are led to the planet by prophecy. Mother and Father’s hopes of founding a peaceful, science-driven society fracture and tilt.

The show cleaves to the classics. The first two episodes were directed by Ridley Scott, legendary director of Alien, Blade Runner, and The Martian. Much of the world will be familiar to sci-fi fans: post-apocalyptic convoys, a slightly sepia desert planet, a plucky and rebellious boy, gloopy space food, succulents standing in for alien plant life, androids who are considered sentient by some and disposable, unfeeling tools by others. It’s a few shades of Star Wars, a smidgeon of The Matrix, and a heaping spoonful of Battlestar Galactica, especially when it comes over all religious. (Granted, whatever higher power is at play in Raised by Wolves, it’s not nearly as cool as Battlestar’s. Less “All Along the Watchtower” and more immolation and traumatized pregnant children. Petition for sci-fi-fantasy HBO to take a break from sexual assault plots.) That said, rhyming with the genre’s greatest hits isn’t necessarily a bad thing. If you like those shows, you’re likely to enjoy this one too.

Raised by Wolves’s ghosts of sci-fi past aren’t the most compelling thing about it, however. That distinction is reserved for its uncanny focus on death and rebirth. The high level of religiousness happening basically guaranteed some afterlife talk, but even Kepler-22b is full of it: The tubers they farm can only grow where the bones of some extinct great serpent lay, and what dies there doesn’t always stay dead. Many of the characters grapple with what death really means, if it means anything at all. “At least you’re not intelligent,” Father says to a creepily humanoid mysterious animal he intends to kill for food. “I died once. Death can be very unpleasant when you’re intelligent.” To the Mithraic, Father’s death would mean nothing, and neither would a human atheist’s, because they’re both soulless and unworthy of mourning. Killing, however, can only be performed by military families and renders others unclean. Campion, a boy raised by Mother and Father on Kepler-22b on a vegan mono diet of tubers (scurvy who?), thinks they’re all monsters.

All of this existential hand-wringing eventually forms the show’s central question: Do humans have to be what they have been? Are humanity’s faults—violence, destruction, prejudice, selfishness—written down like prophecy in our DNA, or have we learned them? Is the natural order truly natural, or a convenient bit of scripture to excuse human exploitation? Science fiction, even as it strives to push humanity forward, often suggests that human failings are inescapable and that cruelty is destiny, sometimes completely by accident. In Raised by Wolves, a white boy is the special one who survives when girls and children of color die. Android servants, “generic service models,” and jailers (jailers!) are all Black, while white, blonde, blue-eyed near-omnipotent Mother flies around posed like Jesus on the cross. What science fiction has imagined has always been limited by history and context and who is allowed to imagine it, as has society. Let’s hope it doesn’t actually take the apocalypse and ascendency of tuber eating to build a better future.