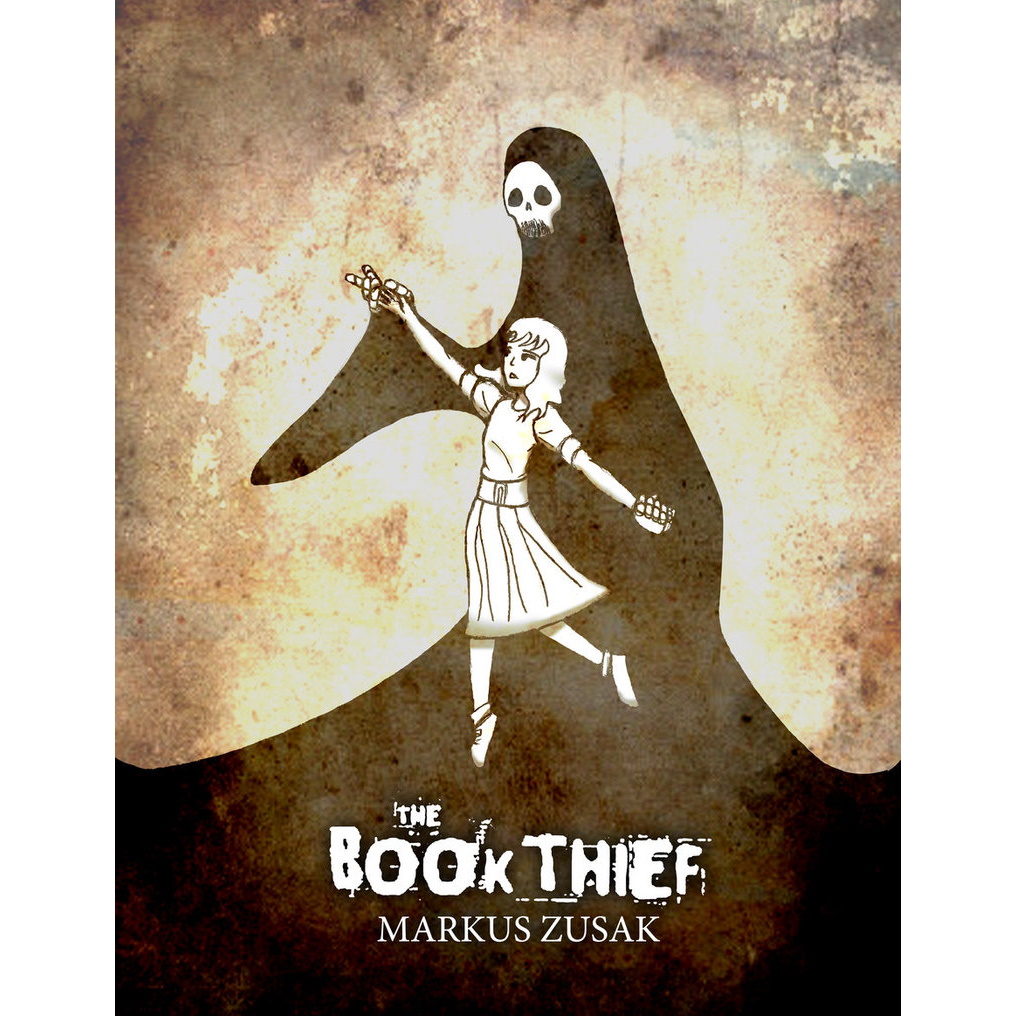

The Book Thief

9/10 from me for this book. It's beautiful and harrowing and did I say beautiful? The reviews from the NY Times and Guardian are actually quite useless, so thanks to Shannon from Goodreads instead! :: Set in Germany in the years 1939-1943, The Book Thief tells the story of Liesel, narrated by Death who has in his possession the book she wrote about these years. So, in a way, they are both book thieves. Liesel steals randomly at first, and later more methodically, but she's never greedy. Death pockets Liesel's notebook after she leaves it, forgotten in her grief, amongst the destruction that was once her street, her home, and carries it with him.

Liesel is effectively an orphan. She never knew her father, her mother disappears after delivering her to her new foster parents, and her younger brother died on the train to Molching where the foster parents live. Death first encounters nine-year-old Liesel when her brother dies, and hangs around long enough to watch her steal her first book, The Gravedigger's Handbook, left lying in the snow by her brother's grave.

Her foster parents, Hans and Rosa Herbermann, are poor Germans given a small allowance to take her in. Hans, a tall, quiet man with silver eyes, is a painter (of houses etc.) and plays the accordian. He teaches Liesel how to read and write. Rosa is gruff and swears a lot but has a big heart, and does laundry for rich people in the town. Liesel becomes best friends with her neighbour Rudy, a boy with "hair the colour of lemons" who idolises the black Olympic champion sprinter Jesse Owens.

One night a Jew turns up in their home. He's the son of a friend of Hans from the first world war, the man who taught him the accordian, whose widowed wife Hans promised to help if she ever needed it. Hans is a German who does not hate Jews, though he knows the risk he and his family are taking, letting Max live in the basement. Max and Liesel become close friends, and he writes an absolutely beautiful story for her, called The Standover Man, which damn near broke my heart. It's the story of Max, growing up and coming to Liesel's home, and it's painted over white-painted pages of Mein Kampf, which you can see through the paint.

Whenever I read a book, I cannot help but read it in two ways: the story itself, and how it's written. They're not quite inseparable, but they definitely support each other. With The Book Thief, Markus Zusak has shown he's a writer of genius, an artist of words, a poet, a literary marvel. His writing is lyrical, haunting, poetic, profound. Death is rendered vividly, a lonely, haunted being who is drawn to children, who has had a lot of time to contemplate human nature and wonder at it. Liesel is very real, a child living a child's life of soccer in the street, stolen pleasures, sudden passions and a full heart while around her bombs drop, maimed veterans hang themselves, bereaved parents move like ghosts, Gestapo take children away and the dirty skeletons of Jews are paraded through the town.

Many things save this book from being all-out depressing. It's never morbid, for a start. A lively humour dances through the pages, and the richness of the descriptions as well as the richness of the characters' hearts cannot fail to lift you up. Also, it's great to read such a balanced story, where ordinary Germans - even those who are blond and blue-eyed - are as much at risk of losing their lives, of being persecuted, as the Jews themselves.

I can't go any further without talking about the writing itself. From the very first title page, you know you're in for something very special indeed. The only way to really show you what I mean is to select a few quotes (and I wish I was better at keeping track of lines I love).

"As he looked uncomfortably at the human shape before him, the young man's voice was scraped out and handed across the dark like it was all that remained of him." (p187)

"Imagine smiling after a slap in the face. Then think of doing it twenty-four hours a day. That was the business of hiding a Jew." (p.239)

"The book was released gloriously from his hand. It opened and flapped, the pages rattling as it covered ground in the air. More abruptly than expected, it stopped and appeared to be sucked towards the water. It clapped when it hit the surface and began to float downstream." (p.325)

"So many humans. So many colours. They keep triggering inside me. They harass my memory. I see them tall in their heaps, all mounted on top of each other. There is air like plastic, a horizon like setting glue. There are skies manufactured by people, punctured and leaking, and there are soft, coal-coloured clouds, beating, like black hearts. And then. There is death. Making his way through all of it. On the surface: unflappable, unwavering. Below: unnerved, untied, and undone." (p.331)

"After ten minutes or so, what was most prominent in the cellar was a kind of non-movement. Their bodies were welded together and only their feet changed position or pressure. Stillness was shackled to their faces. They watched each other and waited." (p.402)

"People and Jews and clouds all stopped. They watched. As he stood, Max looked first at the girl and then stared directly into the sky who was wide and blue and magnificent. There were heavy beams - planks of sun - falling randomly, wonderfully, onto the road. Clouds arched their backs to look behind as they started again to move on. "It's such a beautiful day," he said, and his voice was in many pieces. A great day to die. A great day to die, like this." (pp.543-4)

Writing like this is not something just anyone can do: it's true art. Only a writer of Zusak's talent could make this story work, and coud get away with such a proliferation of adjectives and adverbs, to write in such a way as to revitalise the language and use words to paint emotion and a vivid visual landscape in a way you'd never before encountered. This is a book about the power of words and language, and it is fitting that it is written in just such this way.

The way this book was written also makes me think of a musical, or an elaborate, flamboyant stage-play. It's in the title pages for each part, in Death's asides and manner of emphasing little details or even speech, in the way Death narrates, giving us the ending at the beginning, giving little melodrammatic pronouncements that make you shiver. It's probably the first book I've read that makes me feel how I feel watching The Phantom of the Opera, if that helps explain it.

And it made me cry.