Tragedy, Comedy & Kierkegaard

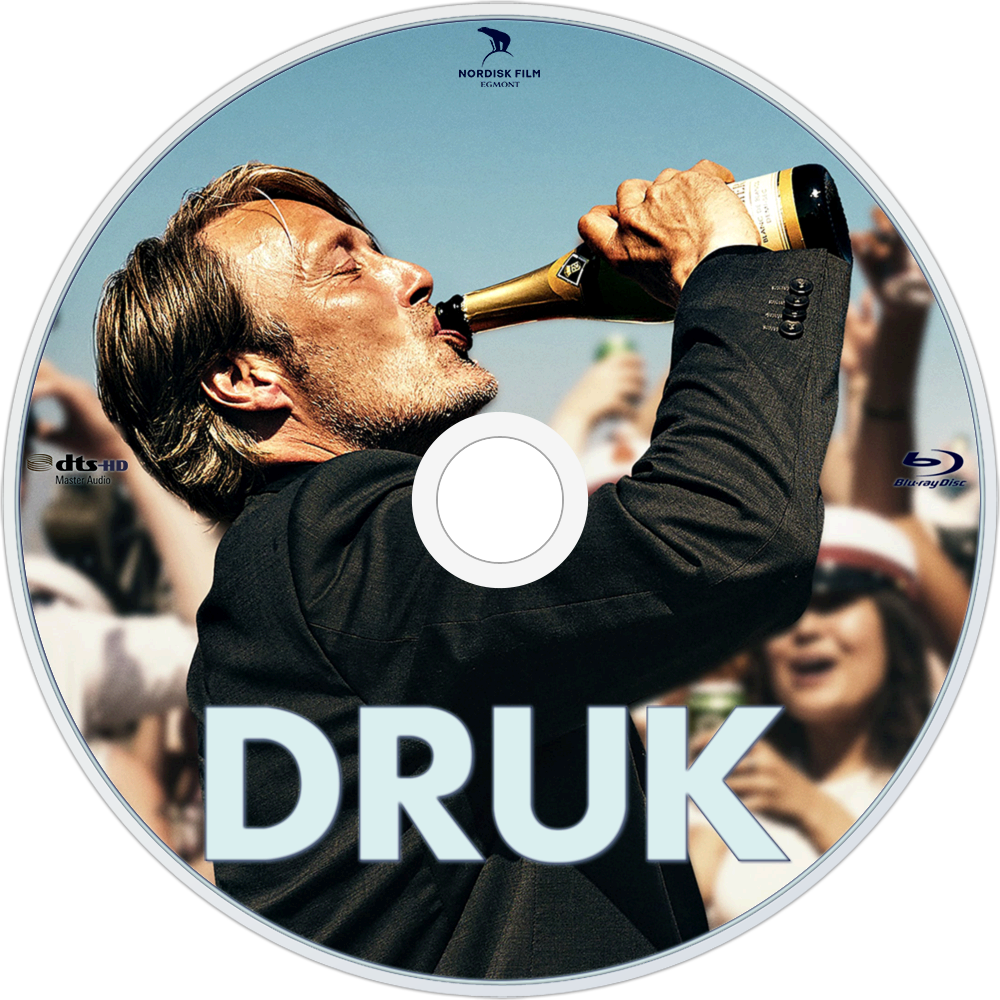

What a fine film this is, with an absolutely brilliant ending! Thanks to Mark Kermode and The Guardian for this review. :: Tragedy, comedy and Kierkegaard collide like the highs and lows of an alcohol binge in Thomas Vinterberg’s latest, which won the Bafta for best film not in the English language, and Oscar for best international feature. Mischievously unruly in tone (“scandalous” is Vinterberg’s preferred word), yet shot through with a flinty shard of sadness, it’s the Danish director’s finest and most personal film since 1998’s Festen – a heady cocktail of ecstasy and grief, buoyed by a superb ensemble cast. At the centre of its maddening spell is a magnificently modulated performance by Mads Mikkelsen, who excelled in Vinterberg’s 2012 drama The Hunt, and offers here the performance of a lifetime in a role that sees him dancing (literally) through the heart of darkness.

Mikkelsen is Martin, a bored, indifferent high-school teacher who, like his closest colleagues, is trapped in the creeping throes of a midlife crisis – a feeling that the glass is now half empty. Inspired by Norwegian psychiatrist Finn Skårderud’s suggestion that the human body has an inbuilt alcohol deficiency, Martin and three close friends embark on a reckless experiment: to see if daytime drinking can help them become better versions of themselves – to learn to live again.

Like the Dogme 95 manifesto that Vinterberg cooked up with Lars von Trier, the rules under which this experiment will be conducted are both severe and absurd. Most importantly, the quartet agree to abandon evening or weekend drinking, restricting their intoxication to the workplace – at least initially. As for the amounts they consume, these will be strictly monitored and recorded in a pseudo-academic document, extracts from which appear on-screen.

At first the experiment yields positive results, with small intakes of alcohol producing big changes (“I haven’t felt this good in ages”). Freed from the anxieties of sobriety, the friends find themselves more lucid, more communicative, more spontaneous. But inevitably, as their intake goes up, so the benefits go down, leaving them spiralling toward self-destruction.

Another Round is dedicated to Ida, Vinterberg’s 19-year-old daughter, who died in a car crash just as production began, but whose vibrant spirit clearly infuses the film. “Having just lost a life,” Vinterberg told me, shortly after being Oscar-nominated for best director, “the celebratory, life-affirming element became extremely important.” Fittingly, while Vinterberg may describe Another Round as existing within the “completely naked, blunt and at times improvised intimacy” of films such as John Cassavetes’s Husbands and A War, by his regular co-writer Tobias Lindholm, there is also a counterbalancing air of the carnivalesque, reminiscent of the exuberance of Federico Fellini.

As for the duality of the Danish character (the anthemic I Danmark er jeg født echoes throughout the film), Vinterberg paints a sardonic portrait of a society torn between well-mannered mediocrity and “going completely bonkers” – a trait (along with sarcasm) that he believes the Danes share with the Brits, perhaps explaining why he felt so at home directing movies such as his 2015 remake of Far From the Madding Crowd.

After the comparative disappointment of Kursk (aka The Command) in 2018, Another Round reminds us of the unique blend of anarchic energy and technical precision that has defined Vinterberg’s best works. It’s a brilliantly ambiguous affair, woozy but precise, profound yet playful, confronting matters of life and death with equal vigour, while ultimately raising a toast to the redemptive power of cinema.