The Hidden Women In Chaos Theory

Thanks to Wired and Joshua Sokol for this article :: A LITTLE OVER half a century ago, chaos started spilling out of a famous experiment. It came not from a petri dish, a beaker or an astronomical observatory, but from the vacuum tubes and diodes of a Royal McBee LGP-30. This “desk” computer—it was the size of a desk—weighed some 800 pounds and sounded like a passing propeller plane. It was so loud that it even got its own office on the fifth floor in Building 24, a drab structure near the center of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Instructions for the computer came from down the hall, from the office of a meteorologist named Edward Norton Lorenz.

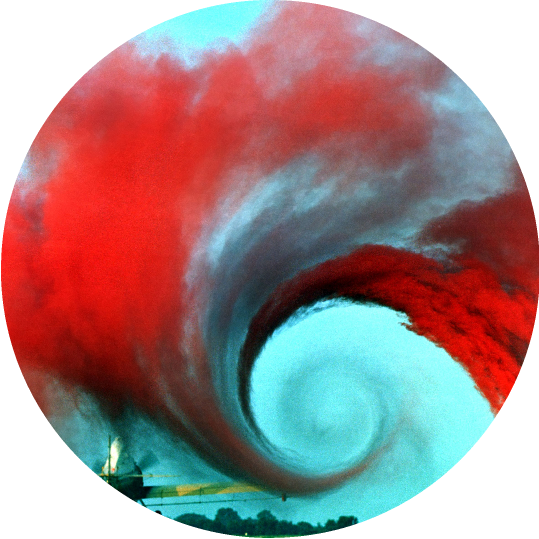

The story of chaos is usually told like this: Using the LGP-30, Lorenz made paradigm-wrecking discoveries. In 1961, having programmed a set of equations into the computer that would simulate future weather, he found that tiny differences in starting values could lead to drastically different outcomes. This sensitivity to initial conditions, later popularized as the butterfly effect, made predicting the far future a fool’s errand. But Lorenz also found that these unpredictable outcomes weren’t quite random, either. When visualized in a certain way, they seemed to prowl around a shape called a strange attractor.

About a decade later, chaos theory started to catch on in scientific circles. Scientists soon encountered other unpredictable natural systems that looked random even though they weren’t: the rings of Saturn, blooms of marine algae, Earth’s magnetic field, the number of salmon in a fishery. Then chaos went mainstream with the publication of James Gleick’s Chaos: Making a New Sciencein 1987. Before long, Jeff Goldblum, playing the chaos theorist Ian Malcolm, was pausing, stammering and charming his way through lines about the unpredictability of nature in Jurassic Park.

All told, it’s a neat narrative. Lorenz, “the father of chaos,” started a scientific revolution on the LGP-30. It is quite literally a textbook case for how the numerical experiments that modern science has come to rely on—in fields ranging from climate science to ecology to astrophysics—can uncover hidden truths about nature.

But in fact, Lorenz was not the one running the machine. There’s another story, one that has gone untold for half a century. A year and a half ago, an MIT scientist happened across a name he had never heard before and started to investigate. The trail he ended up following took him into the MIT archives, through the stacks of the Library of Congress, and across three states and five decades to find information about the women who, today, would have been listed as co-authors on that seminal paper. And that material, shared with Quanta, provides a fuller, fairer account of the birth of chaos.