Worldwide Audiovisual Entertainment vs Cinema

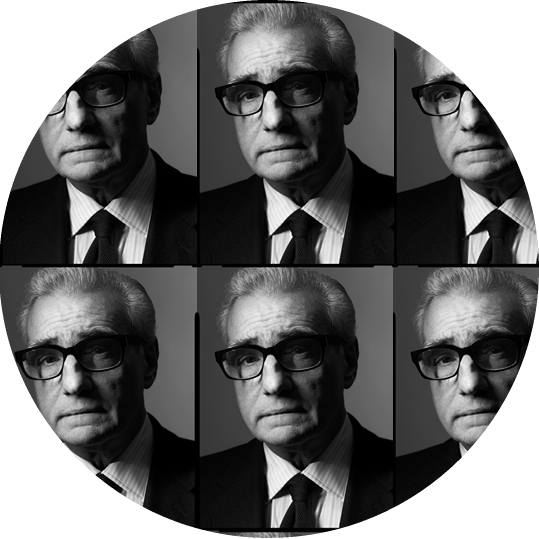

This is a fabulous article from Martin Scorsese:: When I was in England in early October, I gave an interview to Empire magazine. I was asked a question about Marvel movies. I answered it. I said that I’ve tried to watch a few of them and that they’re not for me, that they seem to me to be closer to theme parks than they are to movies as I’ve known and loved them throughout my life, and that in the end, I don’t think they’re cinema. Some people seem to have seized on the last part of my answer as insulting, or as evidence of hatred for Marvel on my part. If anyone is intent on characterizing my words in that light, there’s nothing I can do to stand in the way.

Many franchise films are made by people of considerable talent and artistry. You can see it on the screen. The fact that the films themselves don’t interest me is a matter of personal taste and temperament. I know that if I were younger, if I’d come of age at a later time, I might have been excited by these pictures and maybe even wanted to make one myself. But I grew up when I did and I developed a sense of movies — of what they were and what they could be — that was as far from the Marvel universe as we on Earth are from Alpha Centauri.

For me, for the filmmakers I came to love and respect, for my friends who started making movies around the same time that I did, cinema was about revelation — aesthetic, emotional and spiritual revelation. It was about characters — the complexity of people and their contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures, the way they can hurt one another and love one another and suddenly come face to face with themselves.

It was about confronting the unexpected on the screen and in the life it dramatized and interpreted, and enlarging the sense of what was possible in the art form.

And that was the key for us: it was an art form. There was some debate about that at the time, so we stood up for cinema as an equal to literature or music or dance. And we came to understand that the art could be found in many different places and in just as many forms — in “The Steel Helmet”by Sam Fuller and “Persona”by Ingmar Bergman, in “It’s Always Fair Weather”by Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly and “Scorpio Rising”by Kenneth Anger, in “Vivre Sa Vie” by Jean-Luc Godard and “The Killers” by Don Siegel.

Or in the films of Alfred Hitchcock — I suppose you could say that Hitchcock was his own franchise. Or that he was our franchise. Every new Hitchcock picture was an event. To be in a packed house in one of the old theaters watching “Rear Window” was an extraordinary experience: It was an event created by the chemistry between the audience and the picture itself, and it was electrifying.

And in a way, certain Hitchcock films were also like theme parks. I’m thinking of “Strangers on a Train,” in which the climax takes place on a merry-go-round at a real amusement park, and “Psycho,” which I saw at a midnight show on its opening day, an experience I will never forget. People went to be surprised and thrilled, and they weren’t disappointed.

Sixty or 70 years later, we’re still watching those pictures and marveling at them. But is it the thrills and the shocks that we keep going back to? I don’t think so. The set pieces in “North by Northwest” are stunning, but they would be nothing more than a succession of dynamic and elegant compositions and cuts without the painful emotions at the center of the story or the absolute lostness of Cary Grant’s character.